Burgmüller hairpins

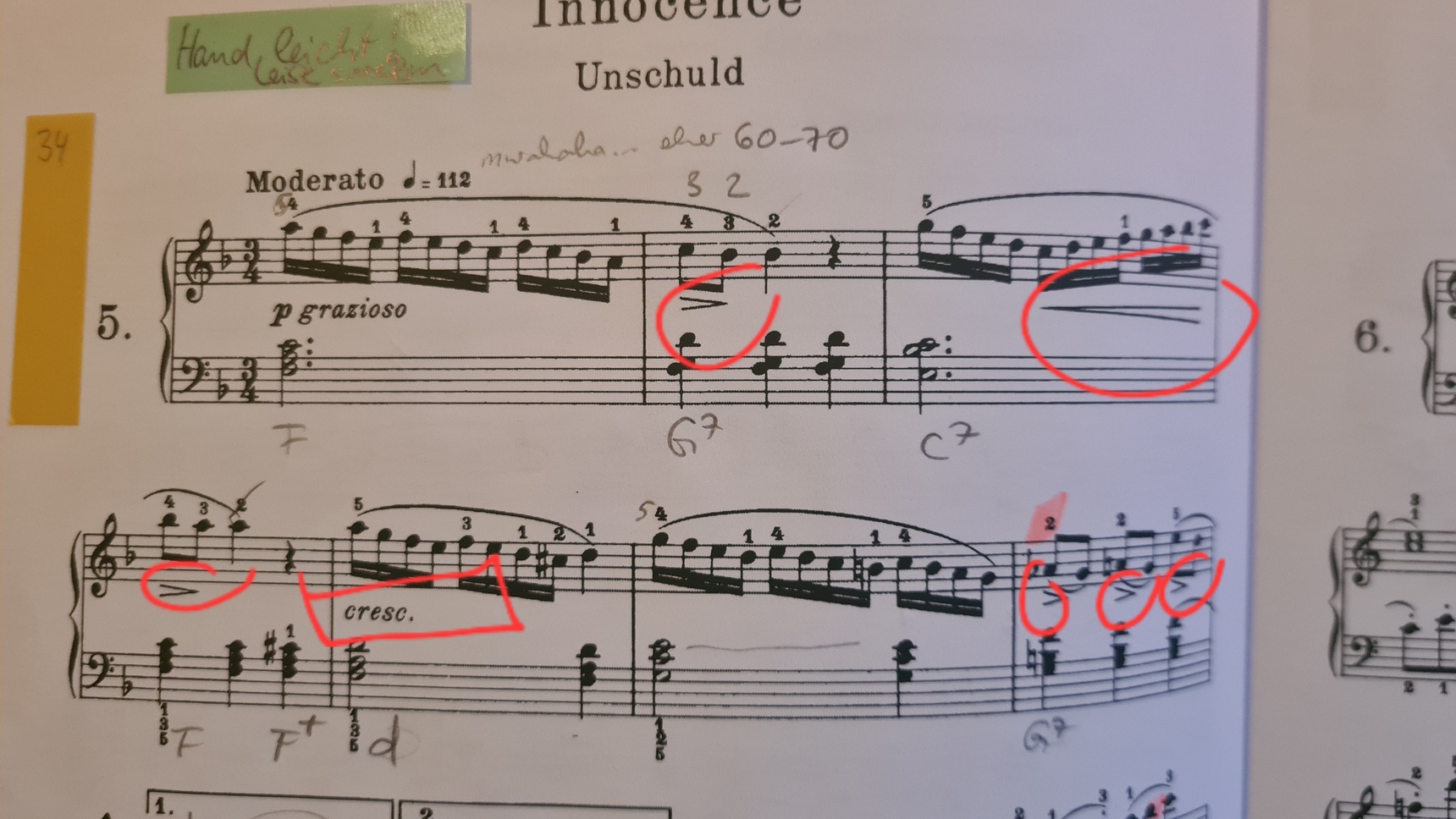

Hello, I have a question about the hairpins in Burgmüller. I read/heard that hairpins in romantic style rather mean rubato than crescendo/decrescendo. Is that always the case, or is it a mix? Does it depend on the composer? How can I make sure I know what the hairpins indicate?

I started Innocence, and here (like also with Chopin and others) I find both hairpins AND "cresc." So I wondered... Shaping phrases with volume changes is so natural, no composer would need to write that down because anyone would do it by instinct. He writes "cresc." where he definitely wants to build up to a clim ax for more than one phrase, so it makes sense to notate that.

But how do I treat the hairpins? Is bar 3 meant to really rush towards the C and then lean into the Bb/A in bar 4. Or would that be ridiculous and overthinking? And bar 7: 3x getting slower, or 3x decreasing volume? Or both? I find this especially interesting because in bar 8 he writes "dimin."

So why would he use 2 ways to describe the same thing... in adjacent bars.. which makes me think more towards getting slower instead of a volume thing...

The B part of the piece only uses p, f, cresc and dimin. instructions, no hairpins at all!

11 replies

-

Replying to your last line -- I don't think so. I think an appoggiatura is intended here, meaning that the Bb is quieter than the C. I'm basing this on both the character of the piece and also what the left hand is doing in the second measure; I think wants to keep going to the C7. My feeling is that using rubato where the closing hairpins are written would disrupt the flow of this piece.

-

These are dynamic markings, not for tempo changes. However, you can stretch the notes at the end of a phrase, such as m. 2 & 4 (play slightly slower). Phrases often end softer, but that doesn't mean you must play slower every time. It all depends on the music.

In m. 5, crescendo means "gradually get louder." When the phrase is long enough, you may speed up a bit to add more excitement but not always. -

Hello.. that's only for Chopin.

-

Dagmar, I cannot answer your question regards specific composers but Seymour Bernstein mentioned the rubato interpretation of hairpins for the romantic period, when he was discussing the Brahms Op.118 No.2. This advice been pure gold for me. I have returned to this piece so many times and now using rubato at the hairpins throughout the piece I have an interpretation that I love and am confident about. Each instance has its own subtle shape, always consistent and I am in control. All I am saying is keep your curiosity going with this and I hope this approach will work for you too.

-

It’s complicated. Just as sforzando means “do something special” not just “louder.” Hairpins mean “give me a little climax.” Depending on context can be a little crescendo, maybe a little faster, maybe a little slower to emphasize an operatic high note. It depends!

there’s a wonderful book about the subject, “The secret life of musical notation.”

-

So I listened to Seymour's post on Chopin several years ago, too, and also found it fascinating and transformative. I'm no expert, but it strikes me that in this piece you might think of the p and cresc markings as indicating the grand overall shape of the work in it's entirety, and the hairpins as "micro" dynamic indicators within each phrase. So between m1 (which starts p) and m5 you're staying within the soft range, with subtle variations at the hairpins. M5 finally gives you permission to expand the dynamic thrust of the piece into a new level of intensity (and further hairpins and markings within the phrase are relative to the new level of intensity you've brought to that section. If you mentally white out the hairpins and intra-phrasal markings, can you see a larger dynamic flow that shapes the whole piece? Just a thought.

-

I see hairpins in most music to be agogic accents/stresses. So for example in bar seven, the three hairpins are just further emphasising the two-note-slurs, or the hairpin in bar 3 opening into the closing hairpin in bar 4 shows you the height of the 2 bar phrase. Basically, as I see it, hairpins are sort of a combination of accents, tenutos, crescendos/diminuendos, and the rubato that Seymour Bernstein describes in his lessons.